As we recognize Plastic Free July and continue our efforts to reduce the use of plastic – and thus reduce the various damaging impacts on our environment, we wanted to take the opportunity for a broader look at the intersection of plastics and biodegradation. The biodegradability of fabrics is a topic Cotton Incorporated has been studying for over a decade.

In recent years there has been a growing focus on microplastics – particles generally smaller than 5 mm – which are generated every time a piece of synthetic fabric is worn and washed. While all fabrics can produce microfibers (or fiber fragments), only synthetic materials release microplastics. Given their small size, what makes these microplastics so concerning?

The dangers of microplastics are difficult to understate – synthetic textiles are now responsible for 35% of the microplastics found in the oceans,[1] and If plastic pollution continues unchecked, there may be more plastic than fish in the oceans by 2050.[2] In a recent study, microplastics were found in human blood and the impacts of microplastics in the human body is a growing area of research in the scientific community.[3]

While we now can definitively prove that natural fibers, like cotton, degrade far more readily in almost any environment compared to synthetic fibers, the research journey is far more complex – and might not be finished yet.

The Beginning

Prior to the more recent attention on microplastics in aquatic environments, Cotton Incorporated was focused on biodegradability in soil. In 2010 we began studying composting with four separate shirts – three cotton shirts with varying treatments, and a polyester shirt. The fabrics were washed 30 times, then allowed to biodegrade in a composting environment. Ninety days later, the polyester shirt maintained 80% of its weight – meaning very little or no biodegradation occurred. In comparison, the three cotton samples had lost between 50% and 78% of their mass – providing evidence to support cotton’s compostability.[4]

Microplastics and Water (and Soil)

As the accumulation of microplastics became more apparent, Cotton Incorporated expanded its research to look at synthetic fiber versus natural fiber decay rates. In 2017, we teamed up with North Carolina State University and examined the biodegradation rates of microfibers from cotton, rayon and polyester, as well as the effect of various washing techniques on microfiber production. We learned that, while cellulose-based fabrics released more microfibers these fiber fragments were able to significantly biodegrade in water whereas the microplastics generated by polyester persisted for long periods of time.[5] This study provided novel and fundamental data to the scientific research community and industry with more than 148 peer reviewed journal citations since publishing in 2019.

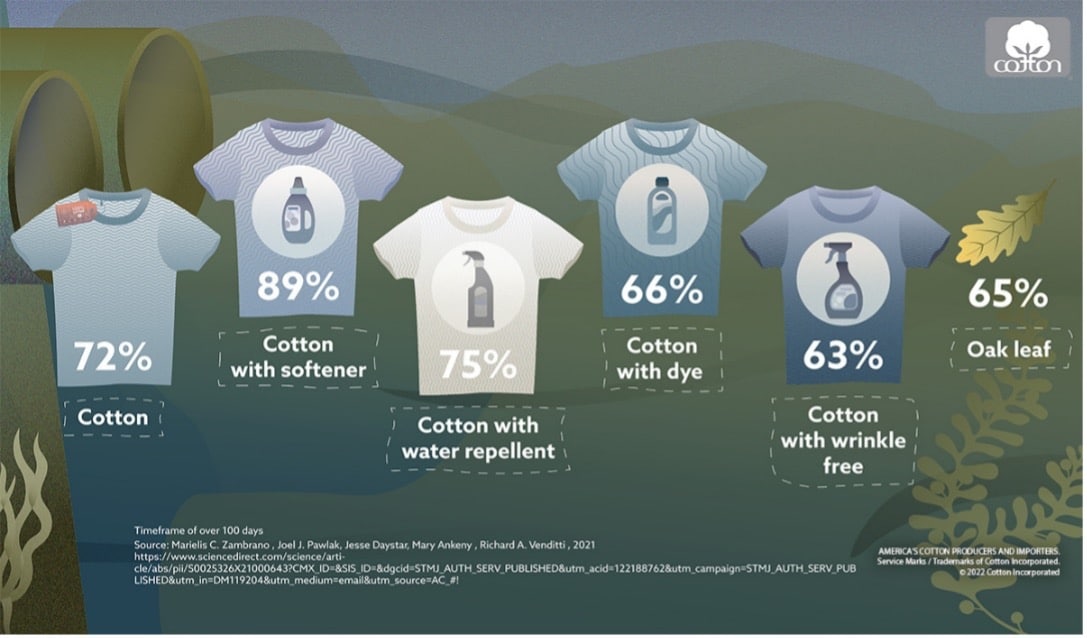

In 2020 and 2021, Cotton Incorporated published studies on various aspects of how microfibers and microplastics degrade in aquatic environments. We learned that regardless of the type of water: lake water, sea water, or “activated sludge” from a wastewater treatment plant– the fundamental truth remains: natural microfibers like cotton readily biodegrade, whereas polyester microfibers essentially do not.[6] We then studied whether various dyes and finishes had an impact on biodegradability. When tested in different aquatic environments, most of the cotton samples degraded by more than 60% in less than 20 days, and some samples degraded by as much as 85% over a 100-day test period. In comparison, every sample actually biodegraded faster and more extensively than an oak leaf.[7]

In 2021, we also returned to the study of biodegradability in soil – looking at the impact of various common finishes. Similar to the aquatic environment study, while the finishes do have some impact on the rate of biodegradation, all cotton fabrics degraded significantly.[8]

The Impact

With all of the variables incorporated into these academic studies, it is important not to lose sight of the common theme: cotton fabric is biodegradable. No matter if you dye it, treat it, compost it, or wash it – and no matter where it ends up – cotton fabrics with the tested fabric treatments (and the microfibers that are created) will biodegrade and will not increase plastic pollution in the environment. Polyester and other synthetic fibers, however, do not break down.

What’s Next

While you may think our journey is done, Cotton Incorporated’s experts still believe there is more to learn, and more to share with the industry. As researchers, it’s important that we continue to evaluate how cotton behaves in different environments and share that information with the industry.

This year, Cotton Incorporated is collaborating with North Carolina State University’s College of Engineering to record how well dyed cotton, bleached cotton, cotton treated with softener, and cotton plus a durable press finish degrade as compared to polyester fabrics in a simulated landfill environment. We’re also working with Cornell University on a denim composting study to help brands develop guidance for new avenues of circularity.

We look forward to sharing what we learn next.

Mary Ankeny

Vice President, Product Development & Implementation Operations

Jesse Daystar – Vice President, Chief Sustainability Officer

[1] Boucher, J. & Friot, D. (2017). Primary Microplastics in the Oceans: a Global Evaluation of Sources. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, https://www.iucn.org/content/primary-microplastics-oceans World Economic Forum. (2016). The New Plastics Economy: Rethinking the future of plastics. 1–36. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_New_Plastics_Economy.pdf

[2] Dalberg and University of Newcastle. (2019). No plastic in nature: assessing plastic ingestion from nature to people. Retrieved from: Plastic ingestion by people could be equating to a credit card a week. The University of Newcastle, Australia. https://www.newcastle.edu.au/newsroom/featured/plastic-ingestion-by-people-could-be-equating-to-a-credit-card-a-week.

[3]Heather A. Leslie, Martin J.M. van Velzen, Sicco H. Brandsma, A. Dick Vethaak, Juan J. Garcia-Vallejo, Marja H. Lamoree, (2022) Discovery and quantification of plastic particle pollution in human blood, Environment International, Volume 163, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2022.107199.

[4] Li, L., Frey, M., & Browning, K. J. (2010). Biodegradability Study on Cotton and Polyester Fabrics . Journal of Engineered Fibers and Fabrics, 5(4), 42–53. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/155892501000500406

[5] Marielis C. Zambrano et al. (2019). Microfibers Generated from the Laundering of Cotton, Rayon and Polyester Based Fabrics and Their Aquatic Biodegradation. Marine Pollution Bulletin 142: pp. 394-407, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.02.062.

[6] Zambrano, M. C., Pawlak, J. J., Daystar, J., Ankeny, M., Goller, C. C., & Venditti, R. A. (2020). Aerobic biodegradation in freshwater and marine environments of textile microfibers generated in clothes laundering: Effects of cellulose and polyester-based microfibers on the microbiome. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 151(January). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.110826

[7] Zambrano, M. C., Pawlak, J. J., Daystar, J., Ankeny, M., & Venditti, R. A. (2021). Impact of dyes and finishes on the aquatic biodegradability of cotton textile fibers and microfibers released on laundering clothes : Correlations between enzyme adsorption and activity and biodegradation rates. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 165(January), 112030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112030

[8] Smith, S., Ozturk, M., & Frey, M. (2021). Soil biodegradation of cotton fabrics treated with common finishes. Cellulose, 0123456789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-020-03666-w